The opposition to the excise on distilled spirits was countered by government action early on. As a result of the protests in western Pennsylvania and the conflicts between the United States and North American Natives, Congress passed the Militia Act of 1792. The Militia Act gave the President of the United States the authority to mobilize state militias to combat danger deemed to be “too powerful to be suppressed by the ordinary course of judicial proceedings.”1

The militia was not immediately summoned by President Washington, although both Washington and Hamilton believed the implementation of the Militia Act to be a feasible option if all else failed. Their readiness to implement the Militia Act can be observed in their correspondence. On the first of September of 1792, while referring to the disturbance in western Pennsylvania, Hamilton wrote to Washington, “if the process of the Courts are resisted, as is rather to be expected, to employ those means, which in the last resort are put in the power of the Executive.”2 Less than a week later, Washington responded to Hamilton stating, “But if, not-withstanding, opposition is still given to the due execution of the Law, I have no hesitation in declaring if the evidence of it is clear & unequivocal, that I shall, however reluctantly I exercise them, exert all the legal powers with which the Executive is invested, to check so daring & unwarrantable a spirit.”3

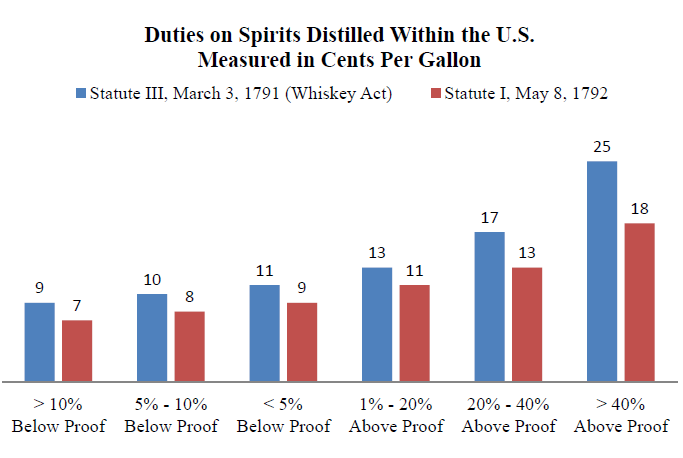

A less forceful course of action in the form of a statute passed on May 8, 1792. The statute lowered the duties on spirits distilled within the United States by two to seven cents per gallon, depending on the proof of the spirit.4 5 A comparison of the duties on spirits distilled with the United States between the statues of 1791 and 1792 is illustrated in the chart below.

The option for forceful execution of the whiskey tax in conjunction with the tax cut of 1792 had little impact. Discontent for the excise began to spread to counties within North and South Carolina. Understanding that the spread of malcontent and violence could spell disaster for the newly independent United States, Hamilton urged President Washington to issue a proclamation. Hamilton believed that quieting the radicals in Pennsylvania would discontinue the spread of disorder in relation to the whiskey tax. In September of 1792, Hamilton wrote to Washington, “Decision successfully exerted in one place will, it is presumable, be efficacious every where.”6 President Washington followed Hamilton’s advice and issued a proclamation on September 15, 1792. Washington’s goal was to make it clear that the Constitution of the United States permitted a tax on distilled spirits and that disobeying the law and authority of the Constitution would be met with penalty. Washington’s proclamation declared,

Now therefore I George Washington, President of the United States, do by these presents most earnestly admonish and exhort all persons whom it may concern, to refrain and desist from all unlawful combinations and proceedings whatsoever, having for object or tending to obstruct the operation of the laws aforesaid; inasmuch as all lawful ways and means will be strictly put in execution, for bringing to justice the infractors thereof and securing obedience thereto.7

Not only was the proclamation issued, but it was also forwarded to the Governors of North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina by President Washington, himself. 8

National unrest was extremely dangerous to the survival of the nation as executive and state powers were still being defined. There was no precedent for handling backlash from citizens or their neglect of constitutional laws. Violence and contempt for the federal government could effectively cripple the newborn republic. The Militia Act, reduction of duties on spirits distilled with the U.S, and the presidential proclamation, were, in all, a peaceful attempt at stopping the spread of an insurgency that could dismantle the country. Washington and Hamilton admitted the need to exhaust all means prior to mobilizing the militia; however, the implementation of the Militia Act would prove to be a necessary option as the state of agitation within western Pennsylvania increased.

- “Militia Act of 1792,” Constitution Society, accessed November 28, 2013, http://www.constitution.org/mil/mil_act_1792.htm. ↩

- Harold C. Syrett, ed., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. XII (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1967), 312. ↩

- Christine Sternberg Patrick, ed., The Papers of George Washington Presidential Series. Vol. 11 (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2002.), 76. ↩

- Statutes at Large, 1st Congress, 3rd Session, 203, accessed 21 November 2013, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.db&recNum=326. ↩

- Statutes at Large, 2nd Congress, 1st Session, 267-268, accessed 21 November 2013, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=001/llsl001.db&recNum=390. ↩

- Harold C. Syrett, ed., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. XII (New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1967), 346. ↩

- Christine Sternberg Patrick, ed., The Papers of George Washington Presidential Series. Vol. 11 (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2002.), 123. ↩

- Christine Sternberg Patrick, ed., The Papers of George Washington Presidential Series. Vol. 11 (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2002.), 165. ↩